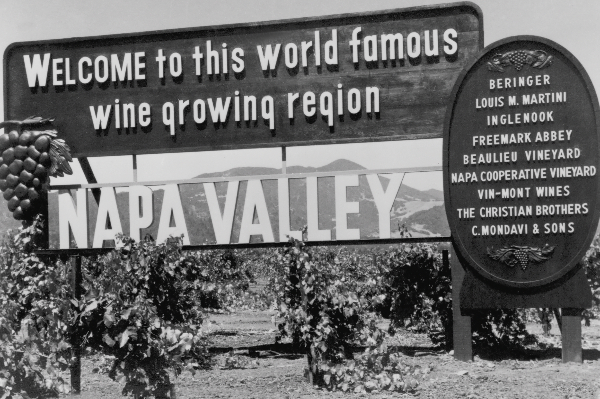

No one could have known it at the time, but the formal adoption of the Napa Valley Agriculture Preserve in 1968 was one of the key factors in allowing this beloved region to become world-renowned for winegrowing.

What on the surface looked like a novel set of citizen-determined zoning ordinances has, for more than half a century, saved some of the finest vineyard land in America, while preserving the open space and natural beauty associated with other national treasures.

Contrary to how it may seem today, Napa Valley’s role as America’s preeminent winegrowing region, and as a bastion of agriculture at the highest level, wasn’t always a foregone conclusion. It took the foresight, bravery and tireless work of a generation of Napa visionaries in the 1960s to set the stage, and the diligence and dedication of subsequent generations, to keep Napa Valley’s vineyard vistas going the way of the Joni Mitchell song lyrics to “pave paradise to put up a parking lot.”

THE GREATEST NAPA VALLEY GENERATION

In the 1950s, Santa Clara was one of the top agricultural counties in the Bay Area. “And then, boom: It’s just like somebody flipped a switch and the subdivisions and the shopping centers and the office parks” started going up, explains Hugh Davies, President of Schramsberg Vineyards.

As the son of the late Jack and Jamie Davies and the president of the board of the Jack. L. Davies Napa Valley Agricultural Land Preservation Fund (JLD Ag Fund), Davies is one of many second- and third-generation vintners working to protect Napa Valley and to keep the vision of their parents and grandparents alive.

“There were enough people in Napa Valley in the mid-’60s, including my father, who had seen what could be overdeveloped so quickly. This drove them to come up with a hard-won plan, ultimately the Napa Valley Ag Preserve, recognizing that Napa Valley had unique properties for growing fine wine grapes,” says Davies.

This landmark set of zoning laws established agriculture and open space as the best and highest use of unincorporated county land from Napa to Calistoga, encompassing the valley floor and foothills. The ordinance dictated that the only commercial activity allowed in these areas was agriculture and set minimum lot sizes that prevented further subdivision of land parcels.

Since its inception when 26,000 acres were protected, not one acre of land in the Ag Preserve has been lost; in fact, it has expanded to more than 32,000 acres.

THE GOOD FIGHT

Passing the Ag Preserve into law wasn’t an easy process. No other legally binding agricultural protection of this kind had ever before been implemented in the United States, and its passage took a massive effort of community education and often fierce debate.

“From what I know … not everybody liked the idea,” Davies continues. “And there were some really tough meetings where this topic was debated.” But the persistence of legends like Jack Davies, Gene Trefethen, Volker Eisele, Dorothy Erskine, Si and June Foote and many others won out, after more than 55 town hall-style meetings and volunteers going door to door to garner community support.

Ultimately, the Napa County Board of Supervisors passed the nation’s landmark Ag Preserve into law. And with its passing dramatically changing the course of how Napa Valley evolved and in doing so, helped to define American wine culture as we know it today.

AN AMERICAN ORIGINAL

After a successful career helming the Kaiser Corporation, Gene Trefethen wanted to purchase land in Napa Valley with his wife, Katie. The year was 1968 and arguments against the adoption of the proposed Ag Preserve were in full-throated expression. There were serious concerns that passage would depress land values, since commercial development was widely assumed to be the best use of the proposed protected acreage.

But the Trefethens didn’t see it that way. They were so confident in the Ag Preserve’s long-term benefits that they predicated the purchase of what would become Trefethen Family Vineyards on its passage.

“Granddaddy had grown up in the Santa Clara Valley, which was becoming the Silicon Valley, before they came to Napa,” says Hailey Trefethen, the third generation of the family in Napa Valley. “They had a walnut farm in Walnut Creek and realized that they had some of the last walnuts there. So, when he came here, he wanted something that was going to stay in agriculture.”

At the time, no one had any way of knowing that in less than a decade Napa Valley would leap onto the world wine stage—the Judgment of Paris was still eight years away—and there was no assurance that growing grapes would be as profitable as developing the land commercially. “There was one way that you got local people to vote for the measure,” Trefethen continues. “To make their land more valuable with the Ag Preserve. You bet on agriculture, which wasn’t something that people were really doing at the time.”

This seems obvious in hindsight, given today’s skyrocketing value of prime Napa Valley land, but it wasn’t the case when it was being debated. Still, Trefethen took a chance, purchased the land once the Ag Preserve was approved and the rest, as the old cliché goes, is history.

AN ONGOING PROCESS

The Ag Preserve was voted into effect more than half a century ago, but it’s far from a static relic of that era. Indeed, over the intervening decades, there have been several extensions to it, both in terms of the parcel sizes permitted within its boundaries, as well as the timeframe through which it will be in force. Most famously, a measure was passed overwhelmingly by Napa County residents in 2008 that extended the Agricultural Lands Preservation Initiative for another 50 years, until 2058.

Still, it’s an ongoing effort. Educating younger generations about both the history of how Napa Valley became synonymous with grape growing in America, as well as the importance of nurturing that land far into the future, is a dynamic priority.

Every year, for example, the JLD Ag Fund awards scholarships to high school students who plan on going into agriculture. “This past year,” notes Rich Salvestrin, owner and director of vineyard and winery operations of Salvestrin, third-generation vintner and a board member of the JLD Ag Fund, “several students were awarded $20,000 to help with their college education.” The goal, he explains, is that “they might come back and be involved in the Napa farming community.”

Another generational advocate is Christiane Eisele, an emergency room physician who after living in New Orleans moved home to Napa Valley. Her family name is synonymous with Napa Valley wine and her father, Volker Eisele, was instrumental in many land use issues as well as the Ag Preserve. As a JLD Ag Fund board member, she helps raise money and awareness of the need to continually move the needle forward in protecting Napa Valley’s agricultural heritage; there’s even an agriculture-based scholarship in her father’s name at Napa Valley College, a source of immense pride.

Her time away has given her a renewed perspective on the importance of looking deeper than the fame of Napa Valley and focusing on what makes it so special: “This is an agricultural community …that’s actually what makes the valley so great,” Eisele says.

And that’s worth protecting, which is what the Ag Preserve has done for more than 50 years and will continue to do so for generations to come.