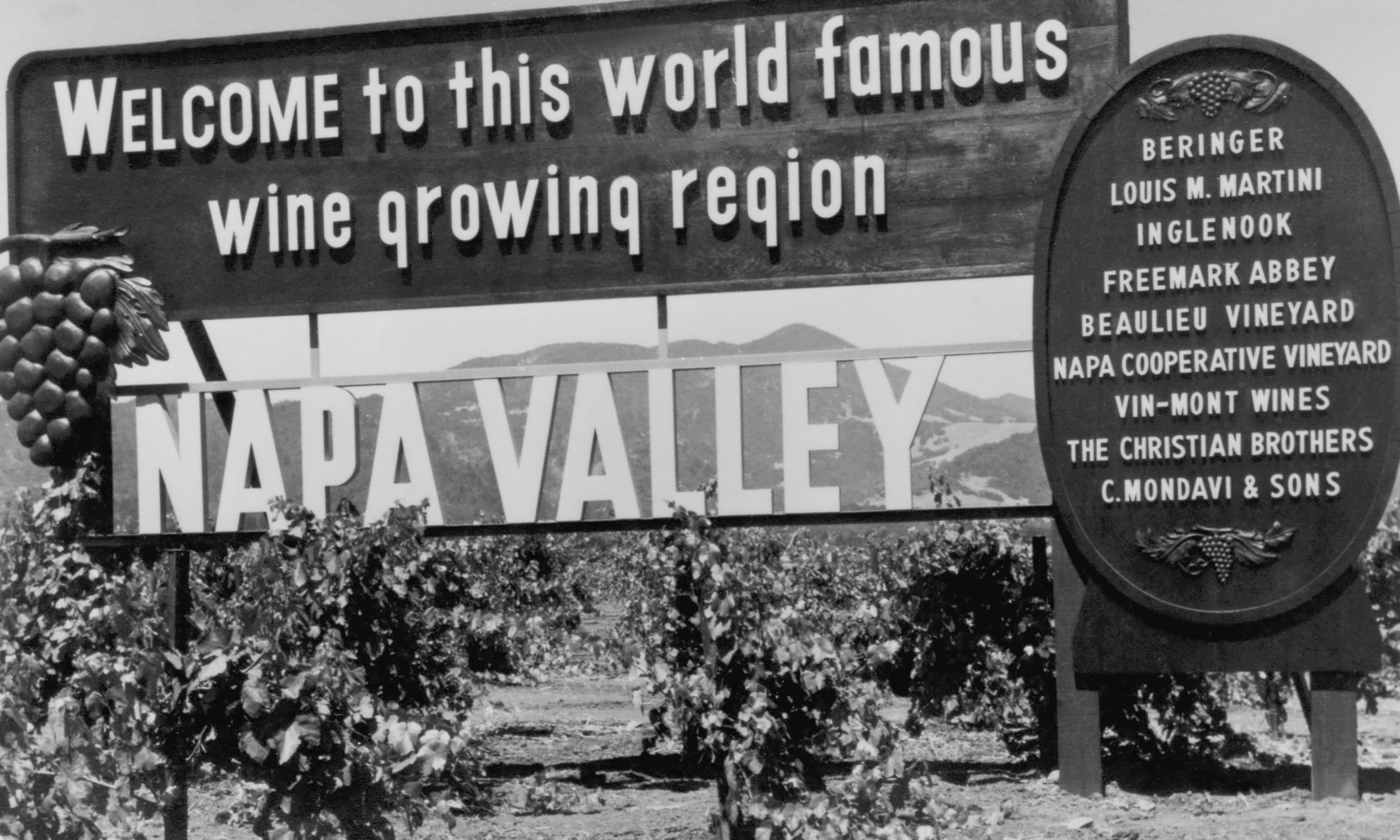

Located a couple of miles north of Yountville on the St. Helena Highway, the iconic “Welcome to this world famous wine growing region Napa Valley” sign has greeted millions of visitors since 1949. At the time, the name of the region was not officially recognized by the United States government. Instead, the area was considered part of Napa County, and the sign was meant to welcome visitors heading north toward long-established wineries such as Inglenook, Beaulieu Vineyard, Beringer Vineyards and Charles Krug.

These wineries are truly historic, considering that 90 percent of the original vineyards planted before Prohibition were abandoned or replaced by fruit and nut trees, hayfields, sheep pastures and other agricultural enterprises in the first half of the last century. This agricultural diversity speaks to the geographical wonderland of different soils, climate conditions and other natural phenomena spread across the Napa Valley floor, mountains and cooler areas near San Pablo Bay to the south. These factors would play a key role in Napa Valley becoming the first AVA—American Viticultural Area—on the West Coast, a designation it earned more than 40 years ago.

Charles Krug’s winery was the first to be established in the sunny area near St. Helena, in 1861, and other pioneers began spreading out to plant successful grape varieties throughout the county. Before Prohibition, world-class wines crafted with fruit grown on the valley floor and higher- elevation areas showed the great potential of the region and provided historic evidence that would eventually help develop the series of nested AVAs between 1983 and 2011.

Robert Mondavi established the first major post-Prohibition winery in the valley, in Oakville in 1966, and other modern-day vintners fueled the growth of new vineyards with an emphasis on Bordeaux varieties. This momentum continued into the 1970s and beyond, resulting in the development of new vineyard sites and wineries and the use of metal tanks and French-oak barrels to replace the ancient redwood casks in the cellars.

In 1976, a major turning point occurred when wines made by Napa Valley producers won over the highly touted French selections at the famous Judgment of Paris tasting. Before that time, there were no written laws in America protecting the name of distinguished wine regions, and it had been common to see the name of the county where the grapes were grown instead of a region. This would have a significant influence on the eventual AVA development to ensure proper labeling designations.

ESTABLISHING THE CRITERIA

It began with the goal to create legal boundaries establishing the Napa Valley AVA. An American Viticultural Area, or AVA, identifies a grape-growing region with shared traits based on geographical features, including identification of soils, climate conditions, elevations and other traits. It is the legal designation that is allowed on the label, which also includes the winegrowing heritage, separating the region from surrounding areas.

To start this formal process in 1978, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms created a petition with criteria that required reports on the soil science, weather conditions and geology of the region; detailed lines and mapping of the boundaries; and a recognized name for the region, based on historical and current evidence.

When the AVA petition was released, the acreage of Napa Valley vineyards was still relatively small, and most were located on the valley floor. Therefore, when the committee of vintners and growers started to map out the geographical boundaries, they had to consider specific characteristics—and allow plenty of room for growth.

Today, the Napa Valley AVA covers a large portion of the area inside the boundaries of Napa County. (Follow along on our pullout AVA map included in this issue.) Along the valley floor, it begins south of the city of Napa and follows the Napa River north until hitting dense forest past Calistoga. The western border follows the edge of San Pablo Bay and then heads north along the ridge of the Mayacamas Mountains to the northwest corner at the top of Mount Saint Helena. In contrast, defining the eastern boundary along the west-facing Vaca Mountains required detailed discussion; it now begins in the low-elevation area east of the city of American Canyon and heads along the ridge due east, toward Lake Berryessa and finishing on the Lake County border.

In 1981, Napa Valley became the first appellation in California and the first official AVA to be recognized on the West Coast. The outcome was a monumental victory for Napa Valley producers and made an immediate impact.

THE GROWTH OF NESTED AVAs

When Napa Valley became an official “appellation of origin,” the focus then began to shift to creating subappellations, or nested AVAs, to distinguish themselves from others. With the small zones on the valley floor already recognized by the names of nearby towns, the first stage of emphasis was to define the distinctive traits and boundaries of the regions in the high-elevation mountains and cool-climate southern section of the county.

In contrast to an individual winemaker’s accomplishments, the creation of an appellation is a group effort that requires lobbying, research and committee participation by growers and wineries from the region.

Dawnine Dyer, who founded Dyer Vineyard in the Diamond Mountain District with her husband, Bill, in 1996, thinks the key to AVA creation is making sure all the stakeholders are in agreement and, if not, to work out disagreements before submitting the preliminary petition to the regulating government agency.

For Dyer—and many other vintners and growers throughout Napa Valley—it starts with being a part of the world-recognized brand that is Napa Valley, followed by the identification with the particular nested AVA. “Our [nested] AVA helps make it clear that members of this small group are associated with distinguished flavors from the mountain,” Dyer explains. “But we’re not trying to homogenize. We are trying to showcase the similar elements that are shared by producers in the region.”

Today, the Napa Valley name represents much more than the vines planted on the valley floor north of the iconic welcome sign. It signifies an expansive matrix of vineyards, with world- recognized brands and 16 nested AVAs, varying in elevation from just above sea level to 2,600 feet above, which all fall within the legally defined boundaries of the greater Napa Valley appellation. Together, this elaborate collection of crops produces high-quality grapes with low yields and concentrated flavors that are used to make some of the most prolific wines enjoyed by consumers and collectors around the globe.